Leaving one's comfort zone - post-mortem on my wiki converter project

This article is a post-mortem on a small project I’ve been working on for the past few months.

The project itself is mundane: I was tasked with converting a MediaWiki archive into a Git repository, with revision history included.

Where it gets interesting is that, while I initially expected to finish the project in less than a week, it ended up taking about twenty days, spread over three months. Over those months, I’ve made mistakes, changed course a few times, realized that not everything had to be written in Rust, and resolved that this would be a learning experience for me.

This post-mortem is an attempt to both share the lessons I’ve learned, and actually figure out what those lessons were. Ducks may or may not be involved.

This is a fairly long post. Jump here if you want to skip all the nitty gritty details and get to the “I learned to not use Rust all the time” part.

The timeline

In June 2023, I was hired by Mill Computing under its sweat-equity system to work on the project’s infrastructure, documentation, and [REDACTED].

The first task I was given was, as I said, converting their private wiki into a Git repository as part of an architecture migration. The pages themselves would need to go from the MediaWiki page format to Markdown.

Being a reasonable, humble person, I obviously told them “Sure, I can do it over a weekend”, which is a perfectly reasonable thing to say to your employer after they give you your first software engineering project. Uuh, moving on.

What was already there

My colleague gave me some code he’d already written, with the advice that I use it to build the repository. His program was a fork of mediawiki-to-gfm, an existing MediaWiki converter written in PHP and based on Pandoc. mediawiki-to-gfm takes an XML export file, which you can produce from https://your-wiki-url.example.com/Special:Export, and produces a directory with converted files with filenames matching the page titles.

My colleague then expanded on that program, using the fact that the export page can also be made to export all previous revisions of a file. He wrote a program that could take an XML export file with revision history included, and produce a repository with one commit per file revision.

He gave me access to his project, and recommended that I run it on all the pages of the wiki; keeping in mind I could use https://your-wiki-url.example.com/Special:AllPages to get a list of pages.

So, all I had to do was run an existing program on a list of pages which I had easy access to, and then upload the result to the company’s server. So I did that, right?

Well… I did not.

What I did instead

Being a reasonable, humble person, I obviously decided to rewrite the whole thing in Rust.

Now wait just a second, and hold your tomatoes. There were a few factors informing my decision:

- When I was given the task, there was a period of a few weeks where I had no access to the company servers because of auth problems. During that period, I couldn’t download my colleague’s code and so I decided to explore my own alternative in the meantime.

- I had misunderstood how the

Special:Exportpage works. I couldn’t find an API endpoint for it, and I thought that meant I would have to export each page by hand, one by one. I didn’t realize that I could give it a list of pages to export all at once. - I had also failed to get the list of pages from the

Special:AllPagespage. Turns out that when you have lots of pages, the list gets paginated. The way it’s displayed on our version of the software is a bit confusing; when I first saw it, I just thought the page wasn’t working. - When I did manage to install my colleague’s php program, I failed to get it to run because of problems with incompatible dependencies.

- I thought I do everything from scratch in a few days, while solving the problems above would take longer.

- Rust is the language I’m most comfortable with, with features for unit testing, snapshot testing, logging, and debugging, all of which I (correctly) thought I’d need for this project.

Hence, I decided to write a Rust converter.

My plan was to:

- Use the Recent Changes API to get the full wiki history as a list of revisions.

- For each revision:

- Use the MediaWiki API to fetch the revision’s new content.

- Write it to disk.

- Use Pandoc to convert it to markdown.

- Commit the new file using

git-oxide.

- Do the above for every single file.

- Making it parallel, using

tokio.

Whew.

Since this was looking to be a non-trivial endeavor with lots of data manipulation, I tried to be smart about it. I would write each part of the pipeline one by one, write a lot of unit tests, and only move forward once I was confident each part was well-tested and working as intended.

To help me write this code, I decided to use both ChatGPT (to get me started on things I didn’t know how to write) and Github Copilot (mostly just to code faster). Here are some examples of questions I asked ChatGPT:

Given a MediaWiki website, can I get the equivalent of the ‘Special:Export’ page using a rest API?

First week

After working a few days on my wiki converter, the main function looked like this:

// 0 - Create repository

// 1 - Fetch all pages

// For each page:

// 2 - Fetch all revisions

// For each revision

// - Write change content to file (create parents if necessary)

// - Commit change to repository

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() -> Result<(), Error> {

let (mut sender, mut receiver) = mpsc::channel(32); // Create an async channel

//let url_base = "";

let client = reqwest::Client::new();

let url = "https://yourwiki.com/w/api.php".to_string();

// TODO - unwrap

let author_data = load_author_data(Path::new("authors.csv")).unwrap();

let repo_path = Path::new("repo");

let mut repository = gix::open(repo_path).unwrap();

let producer =

tokio::spawn(async move { task_get_revisions(&client, &url, &mut sender).await });

let consumer = tokio::spawn(async move {

task_process_revisions(&author_data, &mut receiver, &mut repository).await;

});

tokio::try_join!(producer, consumer).unwrap();

Ok(())

}

The main function sets up some boilerplate, opens the target repository, then starts two parallel tasks with tokio: one which fetches all the revisions from the source wiki, and one which does the whole write-convert-commit dance for each revision. These tasks are each given one end of an async queue so they can communicate. It’s an async main function, which is possible thanks to the #[tokio::main] decorator.

Here is task_get_revisions:

async fn task_get_revisions(

client: &reqwest::Client,

url: &str,

sender: &mut mpsc::Sender<ParsedRevision>,

) -> Result<(), Error> {

loop {

let mut ap_continue_token = None;

let mut pages = fetch_all_pages(client, url, None, ap_continue_token).await?;

for page in &pages.query.allpages {

let pageid = page.pageid;

let mut rv_continue_token = None;

loop {

let mut revisions =

fetch_revisions(client, url, pageid, None, rv_continue_token).await?;

for revision in get_parsed_revisions(revisions.query, page.title.clone().into()) {

sender.send(revision).await.unwrap();

}

rv_continue_token = revisions.cont;

if rv_continue_token.is_none() {

break;

}

}

}

ap_continue_token = pages.cont;

if ap_continue_token.is_none() {

break;

}

}

Ok(())

}

It’s a very dense function, but it’s overall mostly simple: it’s just three layers of loops getting all pages and all revisions for these pages, with some pagination tokens to keep track of.

The interesting work is done in functions like fetch_all_pages, fetch_revisions and get_parsed_revisions. I’ll show you a few of them later.

The line sender.send(revision).await.unwrap(); then sends each parsed revision to the other task, task_process_revisions:

async fn task_process_revisions(

author_data: &AuthorData,

receiver: &mut mpsc::Receiver<ParsedRevision>,

repository: &mut Repository,

) -> Result<(), std::io::Error> {

let authors = &author_data.authors;

while let Some(revision) = receiver.recv().await {

let file_path = get_file_path(&revision.title);

// create parent directories if necessary

if let Some(parent) = file_path.parent() {

tokio::fs::create_dir_all(parent).await?;

}

// execute pandoc command with revision.content as input and write to file_path

let title = revision.title.clone();

let content = revision.content.clone();

spawn(async move {

convert_file(&file_path, &title, &content);

})

.await;

let author_git_data = authors.get(&revision.user).unwrap();

let mut author = get_signature(&revision, &author_git_data);

let mut committer = Signature::new("name", "email", &Time::new(0, 0)).unwrap();

let branch_name = get_branch_name(&revision.title);

let file_path = get_file_path(&revision.title);

create_commit_from_metadata(

repository,

committer,

author,

&branch_name,

&file_path,

&revision.comment,

);

}

Ok(())

}

Again, this is wordy, but the purpose is simple: for each parsed revision, write it, convert it with Pandoc, and commit it. I’ll go into more detail later.

Make a note of the get_branch_name and get_file_path functions. These functions take a page title, with its potential special characters and spaces and slashes, and normalize it into a git branch name or a file path. Here’s get_branch_name, for instance:

pub fn get_branch_name(page_name: &str, namespace: i32) -> String {

let page_name = if namespace == 0 {

format!("Main:{}", page_name)

} else {

page_name.to_string()

};

let page_name = urlencoding::encode(&page_name);

let page_name = page_name.replace(".", "%2E");

page_name

}

Note that, one week into the project, I hadn’t tried running any of the code I’ve shown you so far (except for get_branch_name). Instead, I used a lot of unit tests for the inner functions I alluded to.

For instance, with fetch_all_pages:

pub async fn fetch_all_pages(

client: &reqwest::Client,

url: &str,

limit: Option<u32>,

continue_token: Option<ApContinueToken>,

) -> Result<ApApiResult, Error> {

let limit = limit.unwrap_or(50);

let mut params: HashMap<&str, String> = HashMap::new();

params.insert("action", "query".to_string());

params.insert("format", "json".to_string());

params.insert("list", "allpages".to_string());

params.insert("aplimit", limit.to_string());

if let Some(continue_token) = continue_token {

params.insert("apcontinue", continue_token.apcontinue);

}

let resp = client

.get(url)

.query(¶ms)

.send()

.await?

.json::<Value>()

.await?;

//println!("{:#?}", resp);

Ok(serde_json::from_value(resp).unwrap())

}

#[cfg(test)]

mod tests {

use super::*;

use insta::assert_debug_snapshot;

#[tokio::test]

async fn test_fetch_all_pages() {

let client = reqwest::Client::new();

let url = "https://wiki.archlinux.org/api.php".to_string();

let resp = fetch_all_pages(&client, &url, Some(4), None).await.unwrap();

assert_debug_snapshot!(resp.query);

let resp = fetch_all_pages(&client, &url, Some(4), resp.cont)

.await

.unwrap();

assert_debug_snapshot!(resp.query);

}

}

Most of this code is boilerplate. Some things to note:

- There’s a commented-out println, which hints at how I was debugging this project.

- I used the arch-linux wiki as a data source for debugging, since it was smaller than Wikipedia. I don’t think it made much of a difference.

- I did snapshot debugging thanks to the excellent

instalibrary. I really wish snapshot debugging was a first-class Rust feature, but insta is the next best thing. - The

fetch_all_pagesfunction takes alimitargument, which I used to make the unit tests smaller. Later on I’d incorporate similar limiters into the top-level loops, so that I could run small end-to-end tests.

This approach (writing the small functions first, testing them, and only writing enough glue code to compile) felt very productive, in that I spent most of my time writing the next feature and not struggling with my entire program not working for some reason.

On the other hand, it means my glue code (including the code I’ve shown above) had bugs, and since I hadn’t written tests for the glue code, I had a hard time noticing those bugs, let alone understanding where they came from.

Still, I made some progress.

The following weeks

I got sick in the same period, which I think is part of the reason I didn’t notice the project was ballooning in size. I had spent a week on it and felt barely halfway done, after I’d said it could be finished in a few days.

Still, I didn’t want to give up halfway, and I felt pressured by my previous commitments to the team. I didn’t want to arrive at the meetings empty-handed, and so I decided to work harder and faster on my rust program. We’ll get back to that.

I’m not going to go over everything that went wrong in the project in detail.

In the weeks that followed, I had quite a few problems to solve:

git-oxidedidn’t do the specific things I wanted to do (IIRC it couldn’t stage a file). I had to switch togit2-rs.git2::Repositorycouldn’t be shared between threads. I had to rework my entire tokio architecture.git2would refuse empty committer names and emails, which meant I needed to add defaults for both of those.- The initial

get_file_pathimplementation could have name collisions, so I changed it. - I wanted the program I wrote to be idempotent. That is, I wanted to be able to interrupt execution, then run it again, and have the program keep filling the repository from where it left off, with no duplicated work. There were good reasons to want that, but it added a lot of complexity to the design.

- One bit of complexity was that I wanted to create one branch per file, switch between branches, and eventually merge them all. This is extremely painful with libgit2.

Anyway, after a few weeks of work, I had something that could run reasonably well on ArchWiki and build a partial repository of all their file.

Now the last step would be to run it on the Mill w-

Compiling convert_wiki v0.1.0 (/home/olivier-faure-mill/Projects/convert_wiki)

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 4.31s

Running `target/debug/convert_wiki 'http://private.millcomputing.com/' mill -r 2`

2023-08-25T15:52:49.948354Z INFO task_get_pages{url="http://private.millcomputing.com//api.php"}: convert_wiki: Fetching pages

thread 'main' panicked at 'called `Result::unwrap()` on an `Err` value: reqwest::Error { kind: Request, url: Url { scheme: "http", cannot_be_a_base: false, username: "", password: None, host: Some(Domain("private.millcomputing.com")), port: None, path: "//api.php", query: Some("list=allpages&aplimit=30&action=query&apnamespace=0&format=json"), fragment: None }, source: hyper::Error(Connect, ConnectError("tcp connect error", Os { code: 113, kind: HostUnreachable, message: "No route to host" })) }', src/main.rs:173:35

What? What’s this error? TCP Error 113? That’s not even an HTTP error code! Wha-

Oh. Right.

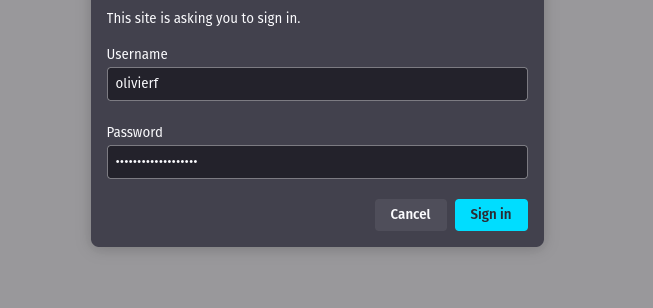

When I try to log in to private.millcomputing.com, here’s what I see:

That means before I could access the Wiki’s API endpoints, I would need to figure out how I can get reqwest to somehow authenticate to the site.

Uuuuuuuuuuuuugh.

Going back to PHP

At that point, I was feeling less sick, my access to the company network was fixed, and I was communicating more regularly with the team.

I checked back in with the colleague who first gave me the task, and asked how to solve the authentication problem.

My colleague then asked a very reasonable question: why exactly was I doing this, and not the approach he’d initially suggested based on parsing an XML dump?

Twenty minutes later, I was left feeling like the worst asshole in the world, as I realized that I had been given the tools to solve this problem and then proceeded to completely ignore these tools so I could work on my own overengineered rewritten-in-rust self-indulgent solution.

Ugh.

Over the next few days, I tried to implement my colleague’s solution using his PHP program. There were still a few problems:

- I still got various build problems from Composer. After a while, I realized all the dependency conflicts were coming from

phpunit, but I didn’t really need unit tests at this point, so I just commented it out. - Running the program on an XML dump, I got some crashes related to invalid file names and empty commit emails.

- The program didn’t handle namespaces (eg

Talk:,User:,File:, etc).

Those were problems I’d already fixed in my Rust program, but the PHP program didn’t handle them.

Again, I considered rewriting the program in Rust.

Going back to Rust

I was a little more wary this time, but it felt like most of the problems I was facing I had already solved in my Rust program, and the things I’d need to port could be ported quickly.

I copy-pasted most of the PHP code into a Rust file in a big block comment, told Copilot “rewrite me this in Rust”, and went from there.

I wrote fewer unit tests this time. I don’t actually think that was a good idea, I think it made me slower, but I just had much less patience for it.

Anyway, I imported an XML parser, retrofitted the code that I’d already written, and ran it on exported dumps.

I quickly ran into a problem where small dumps were fine, but parsing moderately large dumps would fail 5 minutes in, which was a pain to debug. I added a setting to start parsing in the middle of a dump, which made debugging much easier.

Still, I had learned my lessons from the previous attempts. My code was simpler, I didn’t use async programming at all, I tried to do things in a dumb way whenever possible. Progress was overall faster, more regular and less frustrating.

After two days of this, I finally had a fully converted wiki!

Hurray! 🥳

One remaining problem was that links still had a MediaWiki-like formatting. Links in the converted repository would look like this:

[highForm](highForm "wikilink")[S1/Users and groups](S1/Users_and_groups "wikilink")[User:Yost](User:Yost "wikilink")[this link](Foo/Bar Baz! "wikilink")

My first thought was “Let’s solve this with bash commands and regexes!”. I asked ChatGPT for a solution, but what it gave me felt too complicated:

Putting it all together, the commands would look something like:

# Step 1: Remove "wikilink" sed -i 's/\("wikilink"\)//g' *.md # Step 2: Handle namespaces sed -i -r 's/\[([^\]]+)\]\((User):([^ ]+)\)/[\1](\3.md)/g' *.md # Step 3: Handle links without namespaces sed -i 's/_/__/g' *.md sed -i 's/ /_/g' *.md sed -i 's/!/!%21/g' *.md sed -i -r 's/\[([^\]]+)\]\(([^:]+)\)/[\1](Main\/\2.md)/g' *.md

Instead I just wrote another Rust program, again with help from ChatGPT.

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let args: Vec<String> = env::args().collect();

if args.len() <= 1 {

eprintln!("Usage: {} <file1> <file2> ...", args[0]);

std::process::exit(1);

}

let re = Regex::new(r#"\[(?P<name>.+?)\]\((?P<link>.+?) "wikilink"\)"#)?;

for path in args[1..].iter() {

// skip if file is directory

if fs::metadata(path)?.is_dir() {

continue;

}

// skip if file is not markdown

if path.ends_with(".md") == false {

continue;

}

let content = fs::read_to_string(&path)?;

let modified_content = re.replace_all(&content, |caps: ®ex::Captures| {

let link = &caps["link"];

let new_link = get_file_name(link);

let new_link = new_link.to_string_lossy();

println!("Replacing link '{}' with '{}'", link, new_link);

format!("[{}]({})", &caps["name"], new_link)

});

fs::write(path, modified_content.to_string())?;

}

Ok(())

}

I ran that program on my wiki and got converted links. The program didn’t cover all possible MediaWiki links, but a quick skim of the repository suggested it was good enough for what we had.

Now all that was left was converting the media files.

And that… was a bit of a problem.

Back to square one

To summarize the timeline so far:

- First I tried to download all the files using the MediaWiki API.

- Then I realized it wouldn’t work, because my scrapper would fail authentication.

- I instead got all the file contents using the wiki’s

Special:Exportpage.

There’s just one problem: the export page only works for article pages. It doesn’t work for images, videos, spreadsheets, etc.

Which meant I was back to square one: given that I can authenticate in the browser, but I want to fetch some data from the command line, what do I do?

Hard-coding the Authorization header

The first thing I tried was, wait for it, writing a Rust program.

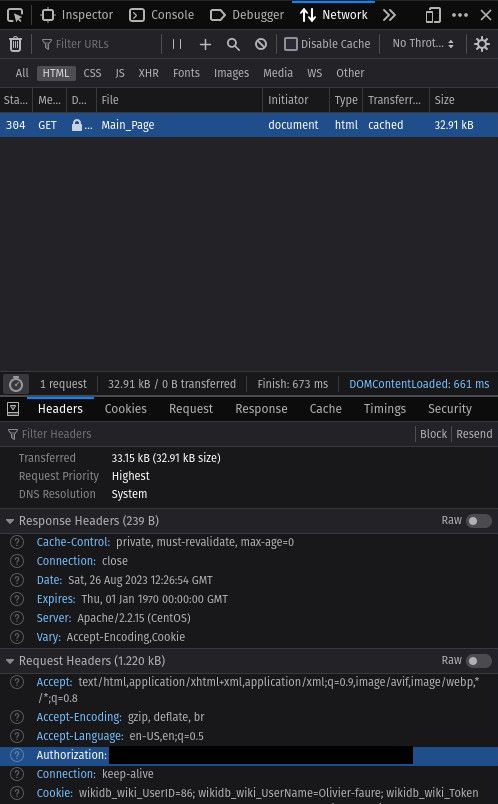

Since I could connect from the browser, I tried to use Firefox Devtools to record a request and see if I saw anything I could copy into my code.

Here’s what the Network tab showed me:

Huh. That Authorization header sounds like what I need!

I tried to write a scrapper, this time making it as non-fancy as humanly possible:

const FILES: [&str; _] = [

"File:2004-02-01-exec-report.pdf",

"File:2005-02-01-exec-report.pdf",

"File:2006-02-01-exec-report.pdf",

// ...

// hardcoded list of all media files

// ...

"File:Tech_Slide_188.png",

"File:Tech_Slide_189.png",

"File:Tech_Slide_190.png",

"File:Tech_Slide_191.png",

"File:Tech_Slide_192.png",

"File:The Future of Performance.pdf",

"File:Windows graphics.png",

];

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

let base_url = "https://your-wiki-url.com";

for file in FILES {

let file_info_url = format!(

"{}/w/api.php?action=query&titles={}&prop=imageinfo&iiprop=url&format=json",

base_url, file

);

let mut headers = reqwest::header::HeaderMap::new();

headers.insert(

reqwest::header::AUTHORIZATION,

"Basic c3dkrjtndlzldmciFOOBARthisISNTtheRealCODE="

.parse()

.unwrap(),

);

let response: serde_json::Value = reqwest::Client::new()

.get(&file_info_url)

.headers(headers)

.send()

.await?

.json()

.await?;

if let Some(pages) = response["query"]["pages"].as_object() {

for page in pages.values() {

println!("Downloading {}...", page.url);

download_file(base_url, page).await?;

}

}

}

Ok(())

}

This code produced yet another connection error, identical to the previous one:

Compiling download_files v0.1.0 (/home/olivier-faure-mill/Projects/download_files)

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 1.98s

Running `target/debug/download_files`

Error: reqwest::Error { kind: Request, url: Url { scheme: "https", cannot_be_a_base: false, username: "", password: None, host: Some(Domain("your-wiki-url.com")), port: None, path: "/w/api.php", query: Some("action=query&titles=File:2004-02-exec-summary-public.pdf&prop=imageinfo&iiprop=url&format=json"), fragment: None }, source: hyper::Error(Connect, ConnectError("dns error", Custom { kind: Uncategorized, error: "failed to lookup address information: Name or service not known" })) }

This showed me that Rust-

Oh my god, it’s Cool Wolf, the public domain royalty-free Original Character! I’ve gotta say, I really like your work and your well-established brand ima-

Wait, what? The wrong URL?

Oh… ooooh.

And the error I got looked similar, but it was a DNS error, not a TCP error!

Well, crap.

Fixing the code with the correct URL now…

Downloading File:2004-02-01-exec-report.pdf...

Downloading File:2005-02-01-exec-report.pdf...

Downloading File:2006-02-01-exec-report.pdf...

Downloading File:2007-02-01-exec-report.pdf...

Downloading File:2008-02-01-exec-report.pdf...

Downloading File:2009-02-01-exec-report.pdf...

Downloading File:2010-02-01-exec-report.pdf...

Downloading File:2011-02-01-exec-report.pdf...

Downloading File:Foo.png...

Downloading File:Bar.png...

What the heck, Cool Wolf? Why didn’t you warn me when I was working on this?

Cool Wolf? Cool Wolf?

Well, moving on.

I feel very silly about this, which is also a benefit of this writing exercise: I get to see things that could have worked had I done them slightly differently.

Anyway, let’s get back to the past days when I thought my Rust scrapper fundamentally couldn’t work.

At this point, it felt very clear to me that my current track wasn’t working, and Rust was not the best language for this project. Even a small project had a non-trivial compile time, which was a handicap when I needed to try lots of small experiments. And given the subject matter (web scrapping), JavaScript was an obvious candidate.

I still couldn’t figure out the authentication problem, though, which meant I had to start thinking seriously outside the box.

Switching tactics: Node.js and Selenium

And by “thinking outside the box”, I obviously mean “asking ChatGPT for ideas”. I asked the following question:

ChatGPT proposed several solutions, among which:

If the content is loaded via JavaScript, curl will not be able to fetch it directly. You might consider using tools like Puppeteer (headless Chrome Node.js API by Google) or Selenium which can interact with web pages including executing JavaScript.

… Huh. The fundamental problem I was trying to solve was taking something I could do manually with my browser, and automating it. Selenium does seem like the right tool for that job.

I started writing short scripts with Selenium. At first I tried navigating to the API endpoints:

console.log(`Downloading '${file}'`);

const file_info_url = `${BASE_URL}/w/api.php?action=query&titles=${encodeURIComponent(file)}&prop=imageinfo&iiprop=url|mime&format=json`;

await driver.get(file_info_url);

await driver.sleep(100);

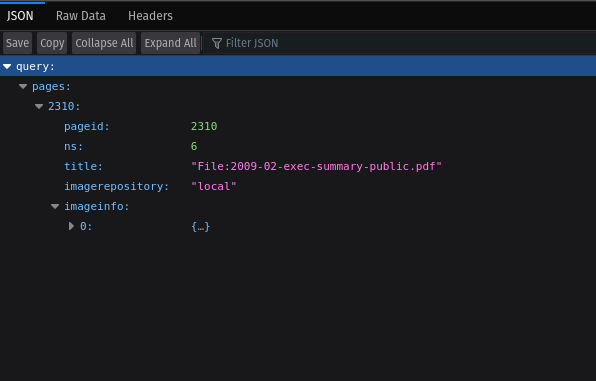

This would display the resulting JSON object in a foldable tree, which was pretty convenient for visualization:

However, the JSON object itself wasn’t really stored directly in any variable I could access. It was displayed (as raw text) in the “Raw Data” tab, so I could retrieve it like this:

const rawDataButton = await driver.findElement({ "id": "rawdata-tab" });

rawDataButton.click();

await driver.sleep(50);

const file_info = JSON.parse(await driver.findElement({ "css": ".panelContent .data" }).getAttribute("innerHTML"));

That worked for JSON objects, but what I fundamentally wanted was to download media files (eg images, spreadsheets), which Selenium didn’t really let you do.

I spent a few hours trying some hacks with the browser.helperApps.neverAsk.saveToDisk preference, which could mark some MIME types as being download-only; with this, you could navigate to a page, and instead of displaying the page, the browser would simply write its contents to the download folder.

I didn’t really manage to get it working, though, and after a while I realized I could use something simpler: the fetch() API.

Calling fetch() inside the browser was simple; the hard part was getting the data back and writing it to disk.

I asked ChatGPT:

ChatGPT’s solution was to encode the file in base 64 and return it from Selenium’s executeAsyncScript.

let base64Data = await driver.executeAsyncScript(`

let callback = arguments[arguments.length - 1];

fetch('${url}')

.then(response => response.blob())

.then(blob => {

let reader = new FileReader();

reader.onload = function() {

callback(reader.result.split(',')[1]);

}

reader.readAsDataURL(blob);

})

.catch(err => callback(null));

`);

I wish it was simpler. Ideally, executeAsyncScript could be like a Web Worker, and have a postMessage() function that would accept any object valid under the structured clone algorithm.

This might be something where BiDi WebDriver; obviously ChatGPT didn’t know about it since it’s more recent than 2021, and it’s still experimental enough that the APIs aren’t documented. If anyone knows more about this, I’m very interested.

(Note from future me editing this: seamless structured clone doesn’t look possible. BiDi WebDriver uses WebSockets under the hood, which are a bit more limited in the data they send than Workers. On the other hand, sending back ArrayBuffers should be possible? I don’t know.)

Anyway, I cobbled together a program using executeAsyncScript, and ran it on the list of all the files I needed to download:

Downloading 'File:2004-02-01-exec-report.pdf'

Downloading 'File:2005-02-01-exec-report.pdf'

Downloading 'File:2006-02-01-exec-report.pdf'

Downloading 'File:2007-02-01-exec-report.pdf'

Downloading 'File:2008-02-01-exec-report.pdf'

Downloading 'File:2009-02-01-exec-report.pdf'

Downloading 'File:2010-02-01-exec-report.pdf'

# ...

Aaaand I’m done!

At that point I have a git repository with all the properly converted pages, to which I can now add all the media files. After which I upload it to the company server, and call it a job well done.

(Technically I’m not getting file histories, but that matters a lot less for media files than for text pages.)

Lessons learned

Yes, thank you, that thought occurred to me several times over the next nine years. I made that principle the centerpiece of my Battle Magic curriculum after I learned its centrality the hard way. It was not the first Rule on the younger Tom Riddle’s list. It is only by harsh experience that we learn which principles take priority over which other principles; as mere words they all sound equally persuasive. Professor Quirrell - HP:MoR

So what did I learn making that converter program?

A bunch of things, as it turns out! I’ll try to trim them to the essentials, but even then, there are lots of essentials.

Here are some honorable mentions I’ve cut for brevity:

- I need to get better at debugging. I did a lot of printf-debugging, which is a hint that I’m not comfortable enough with debuggers. I should train to use debuggers more.

- I need to get better at logging. I actually made a reddit thread about that. I need to follow up on it at some point.

- Tests == Good. I decided early on I’d write lots of tests. That was the first extremely good decision I made. It made me faster, more confident and helped me track down bugs.

- I should test more stuff. The parts I didn’t test (eg glue code, connecting to the Mill wiki) were the ones where all the surprise bugs showed up and set me back days. I didn’t test them because they were out of my comfort zone, but that ended up costing me.

- Sticking to good practices is hard. As the project wore on, I stopped writing tests altogether, and I stopped using version control. It felt less important, like how exercising can feel less important when you get old, because you care less about long-term benefits. Still, short-term benefits alone are worth keeping to good practices.

- Reevaluating assumptions is important. My first estimation was that the scrapper project would only take a few days. That’s an optimistic assumption, but that’s reasonable. When it became clear it was taking longer, and I pushed on anyway, that’s a sin. I should have re-evaluated my assumptions at that point.

On to the big lessons now. first of which is…

Keep things simple

My initial plan for the project was way too complicated: I wanted a multithreaded async program that would fetch files and commit them to git in parallel for maximum efficiency and elegance.

I wanted the program to be idempotent and interruptible, so I could run it if I got errors, I wanted to use git-oxide or git2-rs for better integration, etc.

In retrospect, I was breaking a cardinal rule of software engineering: “First make it work, then make it elegant”.

I should have made everything single-threaded, ran git through std::process::Command (seriously, libgit2 is awful, and git2-rs inherits the awfulness), not even considered interruptibility until I had a working program, etc.

And that’s assuming I should have written a Rust program at all. Which brings us to…

Don’t use Rust all the time

Way back at the beginning of the article, I mentioned my colleague had given me a working PHP program, and I decided to write my own thing in Rust.

The reasons I laid out were:

- Because of server problems, I didn’t have immediate access to my colleague’s program.

- I overestimated how long his approach would take me.

- Trying to run his program, I ran into dependency problems.

- I thought it would be faster to rewrite it.

- Rust is the language I’m most comfortable with, with features for unit testing, snapshot testing, logging and debugging, all of which I (correctly) thought I’d need for this project.

If I’m being honest, the last reason is the only one that mattered, the others were rationalizations. Rust is my comfort zone.

Yet, in retrospect, I realize Deno would have been the better choice: I’m also familiar with it, it has first-class unit testing, snapshot testing and a debugger (I don’t know the logging story though), and most importantly, virtually no build times, which is the most important factor for a project that will require lots of prototyping.

Also, fetching files and parsing JSON and XML are first-class features in JS, whereas they require libraries in Rust.

Rust is in theory more performant, but that really doesn’t matter for a project meant to handle a few megabytes of files. Even if it did matter, I suspect it would have been more efficient to write the project in JS first, and then port it to Rust.

If what I wanted was to write a short program, Rust was the wrong language.

And that’s assuming that writing a program was the right approach at all. Which brings me to…

Try to get data, not a program

My approach during this project was way too holistic.

You know how scientists have a reputation for writing some very bad code that’s impossible to reproduce, because they only need to get their dataset once for their article? I’m realizing software engineers have the opposite bias.

I tried to write an end-to-end program that would do the complete conversion in one go. That means if any individual step failed, the whole thing failed.

What I should have been trying to do is to get the data I needed. In some cases, I didn’t even need to write a program at all.

For instance, I tried to use the MediaWiki AllPages REST API to fetch a list of pages; even though I could navigate to Special:AllPages and copy-paste the list from there in about 30 seconds.

That approach wouldn’t have been scaleable, but I was trying to convert a wiki with less than a thousand pages. I shouldn’t even have been thinking about scalability. Or if I was thinking about it, because I wanted to release a tool to the public, it should have been at the project end, after I made something that worked.

In the context of a small project that didn’t really need to be released, getting data manually was often by far the fastest step, even if it didn’t give me that satisfaction of having automated something.

When I started thinking with that mindset, progress came a lot faster.

Use AI all the time

This was the other extremely good decision I made early on.

In my current setup, I use Copilot and ChatGPT-4. Whenever I have a question about anything or I feel stuck, I ask ChatGPT. When I write stuff in VsCode, I use Copilot.

They are productivity multipliers. This project would not be finished right now if it weren’t for these two tools.

ChatGPT is a good tool for breaking out of your comfort zone. When you want to do something new and you don’t know where to start, ChatGPT is a good first step. It gives you suggestions, knows a lot of tools by name, can give you example code, etc. It provides an essential service to the mind, which is taking a concept that you only know very vaguely about, and giving you concrete examples that you can put your coding hands on.

Talking to ChatGPT felt like an enhanced version of rubber duck debugging, the practice where you explain your problems to someone/something to get a better understanding of them. ChatGPT is not as good as a “someone”, but it’s much better than a “something”. Talking to an inanimate object never really did much for me, but somehow, talking to an AI does.

I think it’s because I know the AI could give useful output, depending on how I phrase my question. It unlocks the part of my brain that thinks strategically about the things I’m trying to express, the process where I dissect a concept to identify which parts are important to communicate and which parts don’t matter. That “thinking-about-what-to-say” process is a big productivity booster in software engineering, and it’s also very fun and motivating on its own.

When you’re working alone or at home, and you don’t have a colleague on the same office floor to talk to, having an AI at hand to unlock that process is a big bonus.

Copilot feels less transformative in itself, and more like a very good autocomplete. It makes you write code faster and spend less time on boilerplate.

There’s some things it’s very suited to, though, like writing unit tests, or translating a program from one language to another.

If anything, it feels a bit underpowered compared to the capabilities I know the model has. It only lets you do auto-completion and chat, but I wish it could also point out mistakes you made, suggest the next line to jump to based on your current edits, etc. VsCode has lots of very powerful affordances for language servers: refactors, assists, diagnostics, inlay hints, etc. I wish Copilot made more use of them.

Anyway, this all confirms my previous beliefs: AI tools are amazing. In the near future, it feels that how productive you can be will largely depend on your ability to integrate these AI tools into your workflow. If you can’t use ChatGPT (say, because of security reasons), consider using a self-hosted version.

A common rebuttal is that there’s a lot of domains where ChatGPT can very easily hallucinate wrong answers, but I haven’t seen that happen too much for code. In fact, for this entire project, I don’t remember ChatGPT ever telling me something that turned out to be factually wrong. And in any case, you can read the code it suggests yourself, and try to run it yourself. In many cases “does it freaking work?” is the only thing you care about.

(Yes, there are caveats. Please don’t have ChatGPT write your ICBM targeting system.)

And now, for my final takeaway…

Selenium is awesome

This was the realization that made me want to write this article in the first place.

Coding with Selenium felt incredibly convenient and understandable. It felt limpid, in a way software development rarely does.

Earlier this year, I wrote an article where I laid out my vision for the future of Rust UI. In particular, I tried to describe my model of “Fearless” Rust GUI, which had the following virtues:

- Iterative: Short iteration cycle, short build times.

- Fixable: Error states are shown on-screen.

- Testable: Unit tests, screenshot tests, benchmarks.

- Inspectable: Affordances, rich logging.

- Replayable: Serializable replay format.

A lot of the features I mentioned wanting are available in one form or another with the combination of browser devtools (especially Chrome DevTools) and Selenium.

JavaScript gives you short initial build times and near-zero incremental build times. Selenium gives you testability, and replayability. Browser devtools give you strong inspection and error-reporting features.

Taken together, you can start a Selenium session, pause in the middle of your script, and run a bunch of commands in the devtools console to see what happens. You can do hierarchical logs, where you only expand the objects you’re interested in. You can even change some values from the console, resume the script, and see how it handles the change.

This is an amazingly visual form of programming, something I’m really not used to seeing! If you tell the browser to go to a page and it gets a 404 error, you can see the 404 page in your browser window. Errors and warnings are displayed in the console, you can inspect the DOM state (and the CSS rules, and everything else DevTools handle these days), you can log custom objects in the console, etc.

The only thing missing at this point is a full record-replay debugger like Mozilla’s rr.

Debugging is usually not this convenient. I know some of this is possible in other debuggers, but Selenium makes it easy in a way that feels a bit magical to me.

So if there’s one thing I’ll remember from this project, it’s this: If I need to do something, and I already know how to do it in the browser, I should just use Selenium to do it.

Conclusion

Whew! Even writing this took longer than I expected. Here’s a quick summary.

The project:

- I wanted to write a converter that would take a wiki and convert it to markdown format.

- First I ignored my colleague’s advice and wrote something that would poll the MediaWiki API.

- Then I realized it didn’t work in my case, and I wrote an XML parser and used manually-produced dumps.

- Then I had to get media files, and I used Selenium to automate retrieving them.

Things I did right:

- Wrote a lot of tests.

- Used ChatGPT and Copilot a lot.

- Used Selenium.

Things I did wrong:

- Didn’t do enough tests.

- Used Rust instead of JavaScript.

- Tried to write a complex program instead of trying to get data.

Those are some pretty universal lessons, I think. They apply to a lot more projects than this small scrapper, and I’m definitely going to try to live by them in future projects.

Note: This post was originally released with the title “When to not use Rust - post-mortem on my wiki converter project”.